Commentary

SPAC-tacular Wall Street’s Latest Casinos

April 15, 2021

This year has started on strong footing for global mergers and acquisitions (M&A). According to Refinitiv, global M&A hit a new record of $1.3 trillion as of March 31st, 2021.[1] What is driving this boom? On the news we have seen many big deals take shape, from GE divesting its business to Canadian Pacific expanding its footprint. But behind the headlines, something else is accelerating M&A activities, especially in the Unites States (US). We are talking about SPAC, which alone represent about 25% of the total deal volume in the US.

The first quarter of this year was also one of the busiest for IPOs, of which, once again, SPACs took the limelight. There were 296 SPACs raising $87 billion, a 20-fold increase over the same period last year.

What is a SPAC?

A SPAC or “Special Purpose Acquisition Corporation” is a vehicle used to acquire a private company and make it public without going through the traditional IPO process. Back in the 1980s, there was something called a “blank check offering”. These were companies focused on finding promising operating enterprises — prospects that sounded great on brokers’ cold call pitches (typical “pump and dump” schemes). Fraud and manipulation was so rampant among these blank check companies, the SEC adopted Rule 419 under the Securities Act of 1933 , “requiring investors’ funds to be held in escrow, filing of a post-effective amendment upon execution of an acquisition agreement, and the return of the escrowed funds if an acquisition has not occurred within 18 months of the effective date of the initial registration statement.”.

David Nussbaum, a Long Island based lawyer and CEO of GKN Securities, understood the new rules would reduce interest from investors. So he reinvented the blank check concept in 1992, and SPACs were born. The SPAC structure allowed for trading, but included many provisions to protect investors — like allowing investors to opt out of the merged company and get their money back once a deal is done.

How do SPACs work?

First, a sponsor raises capital and incurs the cost of an IPO in a new shell company. To make the deal attractive to investors, the units are usually priced at $10 each and provide a warrant to buy more shares. The sponsor then has 12 to 24 months to find the target. If no target is found, or if the investors decide to vote “no” on the deal, the holders can redeem their investments.

We have seen this movie before

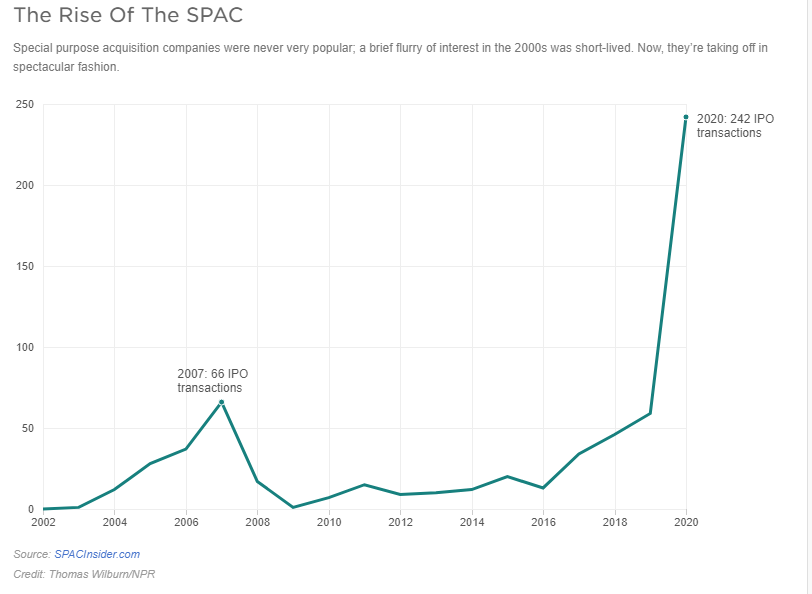

SPACs are in their third decade of existence. In the early 1990s, they were marketed as vehicles that helped small companies go public, while offering outsized favourable terms to their sponsors. In the late 90s, SPACs took a back seat. After all, why would a company do a reverse merger when you could easily raise money during the tech bubble? SPACs enjoyed a renaissance in late 2002, peaking at 66 IPOs just before the great financial crisis. They reappeared in early 2016, and have been going strong ever since. According to SPAC Analytics, in 2020, SPACs were 55% of IPOs, compared to 4% in 2013. So far this year, SPACs represent 79% of total IPOs.

SPACs versus a traditional IPO

SPACs are a pure genius way of going public. Since there is no identified target, a sponsor’s prospectus has no information about the business or the strategy. On the other hand, an IPO roadshow raises a lot of questions and invites a lot of scrutiny from investors.

In an IPO, there is no guarantee on the final valuation of the company. With a SPAC, the IPO has been done, and you have negotiated the valuation of your company with the sponsor. Plus the due diligence required for a merger is much less than SEC requirements for a regular IPO.

Cost could be another key factor. An IPO can cost anywhere between one to seven percent in fees for investment banks. With a SPAC, the underwriter may charge about five to six percent. However, there are other fees associated with the merger, which can end up being almost 20-25 percent of the total money the sponsor may raise.

Why are SPACs so popular?

A recent Wall Street Journal article counted 61 sports-related SPACs formed this year alone, compared to just five in 2019.[2] Athletes from Serena Williams, Stephen Curry, Naomi Osaka, Tony Hawk, Colin Kaepernick, and even Shaquille O’Neal, have shown interest in SPACs.

Everyone loves money, especially free money. SPAC founders and sponsors generally get about 20% of the shares of the SPAC as a fee for raising capital, finding the target, and, of course, giving it their brand name. Hedge Funds like it because they can use leverage to buy SPACs and also get preferential access to SPAC deals at the $10 share price. Everyone else has to wait and likely pay a higher price.

Most investors don’t read the annual reports of the companies they own, so they miss out on the fine print in the SPAC prospectus. For example, many are unaware of the lock-up period, which can be anywhere from six months to a year. Once the lock-up period is over, the floodgates open and add pressure to the stock price.

The clock is ticking?

SPACs don’t have time on their side because there is a limited window to close a deal. Targets are well aware of this restriction. They also know that a SPAC is required to spend at least 80% of its assets on a single deal. So the target always has the advantage. SPACs are paying a median price-to-sales ratio of 12.9, compared to 4.1 paid by other companies, according to 451 Research.[3]

SPAC-mania has been going on for a few years now, which means there is a lot of capital chasing deals, combined with ticking clock syndrome, which signals an inevitable decline in deal quality. We could easily see the SPAC bubble go bust once again.

How have SPACs performed historically?

A team of researchers analyzed completed mergers from January 2019 and June 2020, and found that SPACs lost 12% within the first six months, and dropped 35% on average after the first year. Bain & Co looked at 121 SPAC mergers from 2016 to 2020 and concluded that “more than 60% have lagged the S&P 500 since their merger dates, and 50% are trading down post-merger”. The other 40% are trading below the $10 IPO price.

Portfolio Impact

Regulators like the SEC are beginning to take a closer look at SPACs. SEC recently issued an investor alert pointing out that just because celebrities are backing SPACs doesn’t mean retail investors should follow suit.

At Global Alpha, we do not invest in SPACs. Our focus is on finding high-quality companies with defensible business models and strong balance sheets that should outperform the small-cap benchmark.

[1] https://news.yahoo.com/deal-making-smashed-records-q1-141243172.html

[2] https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-celebrities-from-serena-williams-to-a-rod-fueling-the-spac-boom-11615973578

[3] https://usa-latestnews.com/technology/with-valuations-on-us-startups-skyrocketing-spacs-are-starting-to-shop-overseas/